Natural History

A common myth is that colonizers of the Southeastern Piedmont reached a vast, unbroken forest. Some have claimed that a a squirrel could cross the Piedmont from mountains to the coastal plain and “never have seen a flicker of sunshine on the ground” (J. T. Adams 2012; as quoted in Brown et al. 2000). Recent academic literature refers to the pre-colonial Piedmont region as “Southern Forest” (e.g., Sanderson et al. 2008). Even in Field Guide to the Piedmont, author Michael Godfrey (2012) writes:

This is what I see in the Piedmont of 300 years ago: the canopy claims the direct sunlight completely by filling every gap with a broad-leaved parasol, cantilevered aloft. No part of the jade awning is within one hundred feet of the ground.

A more accurate biogeographic depiction of the historic Piedmont region is a mosaic of many habitats including forest, savanna, and what we now call the Piedmont Prairie.

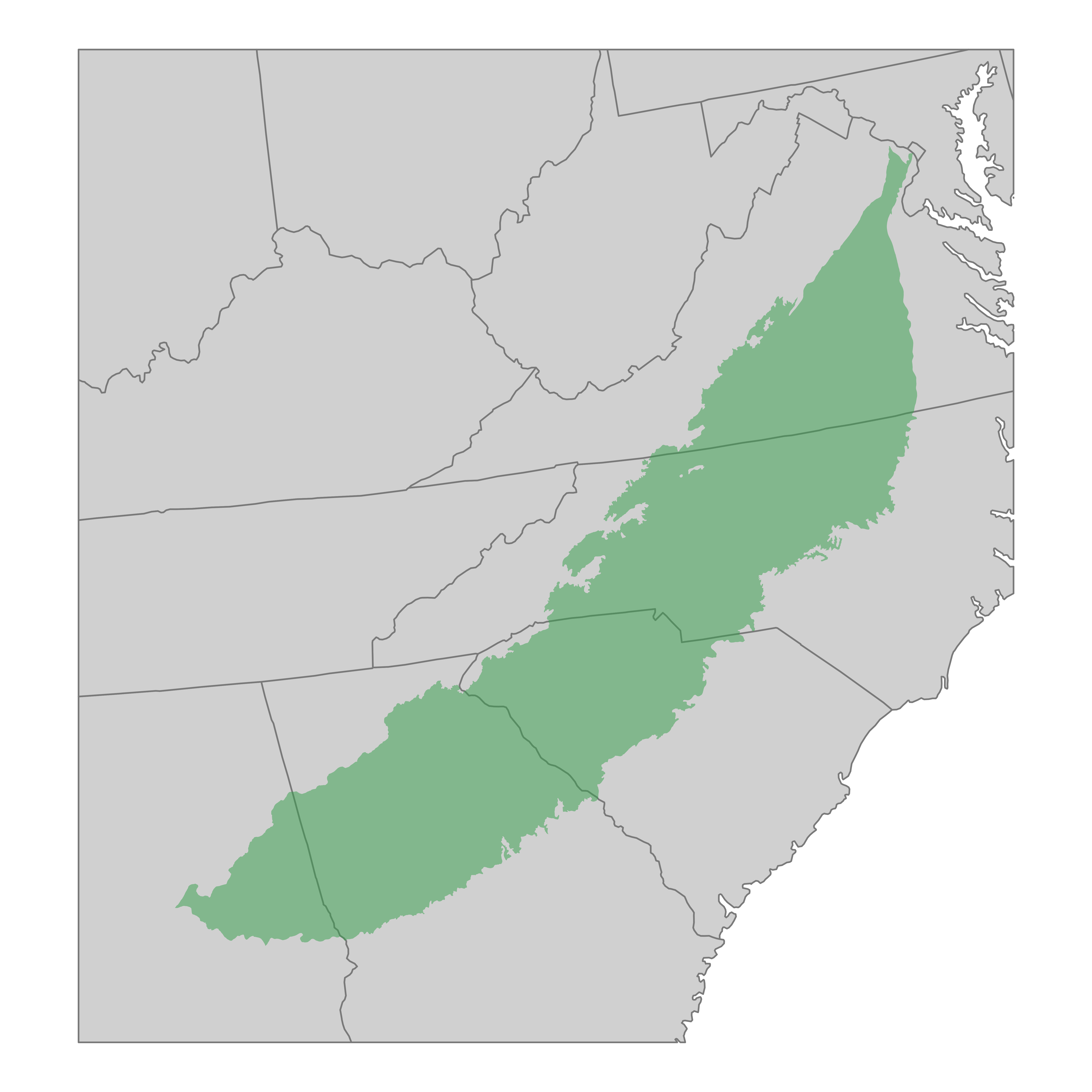

The US Environmental Protection Agency defines the Piedmont Ecoregion as extending from near Montogomery, AL northeastward across Georgia, the Carolinas, and Virginia to Washington, DC. The Atlantic Seaboard Fall Line defines the region’s eastern border, and to the West, the Appalachian Mountains rise out of the Piedmont’s rolling hills.

Piedmont Ecoregion

The precise extent of prairie-like habitat prior to European settlement is unknown, but ample historical evidence suggests open habitat was common. In a seminal monograph on historical vegetation patterns in the Southeast, Rostlund (1957) writes:

On a vegetation map of the ancient Southeast, if such a map could be constructed from the early records, there would be some areas in dark green color to show the dense and mature forests, other areas in light green to represent the open woodlands, and the map would be liberally flecked with yellow to indicate the scattered tracts of open country.

These “yellow flecks” would have included areas of Piedmont prairie.

Prairie origins

Factors that are thought to have contributed to the formation and maintenance of open habitat in the Piedmont include soil type, Native American land-use practices, fire, and grazing by large herbivores. These are briefly described here, though the relative contribution of each factor to sustaining prairie habitat probably varied depending on the locale and its vegetation community.

Soil type

Noss (2012) details many endemic plants and plant communities in the Southeast that survive in large part due to the specific soil characteristics where they are found. Indeed, the Southeast is one of the most species-rich regions in the world in terms of grassland biodiversity. Davis et al. (2002) associated several prairie remnant sites with characteristic clay soils common in the Piedmont. A dense clayey soil could impede tree root growth, especially during dry summers.

The Piedmont does have open habitats such as the Piedmont Hardpan Forest dependent on specific soil types. However, the degree to which edaphic (soil) factors maintained large tracts of open habitat historically is an open question. Since most of the Piedmont has been plowed in the past 400 years, where we find prairie remnants today may not be representative of the Piedmont prairie’s historic range and soils.

Indigenous Land Use

A recent report by the North Carolina Natural Heritage program (Robinson 2020) found “that while edaphic conditions play a role in the distribution of prairie/savanna associated plants, it is the prevention of canopy closure through anthropogenic activity that is most closely associated with the distribution of these plants at the present time.” The Piedmont region was a long-thriving center of human activity prior to European settlement, supporting an extensive trade network and largely agricultural societies. Indeed, Dobbs (2009) argues that the trade routes left by the indigenous people (after disease had extensively depopulated the Piedmont) set the “initial conditions” upon which early Piedmont settlers built their society.

Early explorers and settlers of the Piedmont describe large open areas maintained by Native Americans. Brown et al. (2000) cite several historic records of prairie-like regions of the Virginia Piedmont, including one Robert Beverley who described “large Spots of Meadows and Savanna’s (sic), wherein are Hundreds of Acres without any Tree at all; but yield Reeds and Grass of incredible Height.”

Fire

While many of the Piedmont habitat types today do not share the same dependence on fire as the Long Leaf Pine savannas of the Coastal Plain, remnants of fire-adapted habitats such as Post Oak savannas and prairies suggest fire was historically an important driver ecological patterns in the Piedmont. Prior to colonization, fires – both man-made and natural – occurred regularly in much of North America. Frost (1998) estimates a presettlement fire frequency of every 4-6 years for most of the Piedmont. Native Americans also used fire as a primary means to clear and open areas (Williams 2003).

Today, conservation-minded property managers use fire as a critical tool to maintain Piedmont Prairies. The following short video shows how fire is used at a small Piedmont Prairie patch at Sarah P. Duke Gardens in Durham, NC:

Herbivory

Historical evidence suggests American Bison (Bison bison) ranged widely across the American Southeast during at least the 16th and 17th centuries (Rostlund 1960). To have been successful, bison would have needed large tracts of open, grassy areas. Bison were a keystone species in the Tallgrass prairie of the midwestern plains, their grazing having had profound effects on the ecosystem (Knapp et al. 1999).

Were bison a keystone species in the Piedmont, maintaining and expanding prairie habitat? We don’t know how long the bison’s range extended over the Piedmont. But given the volume of herbaceous plants needed to sustain herds of bison, their effect must have been profound.

Biodiversity

From a distance, grasslands may appear to have little biodiversity, hosting only a few, highly abundant species. Close inspection tells a different story. In fact, grassland habitats can be among the most biodiverse places on earth (Wilson et al. 2012; Risser 1988). Tompkins et al. (2010) inventoried over 200 species on a single 2.8 hectare Piedmont prairie site.

Several rare or endangered species find refuge in Piedmont prairie habitats. Schweinitz’s sunflower (Helianthus schweinitzii) is a federally listed endangered species and found only in the South/North Carolina Piedmont. Smooth purple coneflower (Echinacea laevigata) is another federally listed species that prefers open and sunny habitats.

Finding prairies today

While ample evidence shows prairie and savanna habitats were once more widespread in the Piedmont, where can the prairies be found today? Besides a handful of prairie sites managed for conservation (see map below), many of the best prairie habitats are hidden in plain sight! The regular mowing and removal of woody species makes roadsides and other rights-of-way ideal refugia for prairie species in the Piedmont (N. Adams 2012).

Conservation

Awareness of the Piedmont prairie’s conservation value has risen in recent years. While the Piedmont region is highly fragmented and development pressures are only increasing, there are positive signs of conservation of this habitat. A number of prairie demonstration and restoration sites have been created. Organizations such as the Southeastern Grasslands Initiative have spearheaded initiatives to identify, protect, and restore Piedmont prairie.